Improving Health Equity by Giving Every Child the Best Start in Life

November 8, 2023

The issue

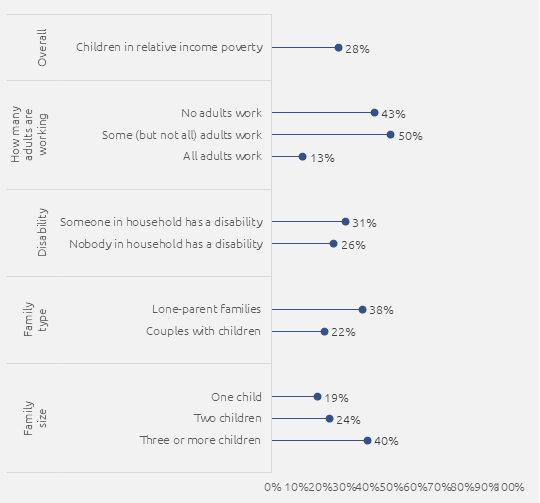

Children have the highest risk of poverty out of all age groups in Wales: nearly one in three or 28% of children are living in relative income poverty, and children in larger, lone-parent or workless families are at particularly high risk.

Relative income poverty is defined as living in households that earn below 60% of the median UK household income (after housing costs). The key indicator of child poverty uses this definition, but Welsh Government also uses a wider set of key indicators, including:

- Percentage of children living in relative income poverty where at least one adult is working (after housing costs).

- Percentage of children living in workless households.

- Percentage of babies (live births) born with a low birth weight (defined as under 2,500 grams).

Children’s risk of being in relative income poverty in Wales (FYE 2020 to FYE 2022)

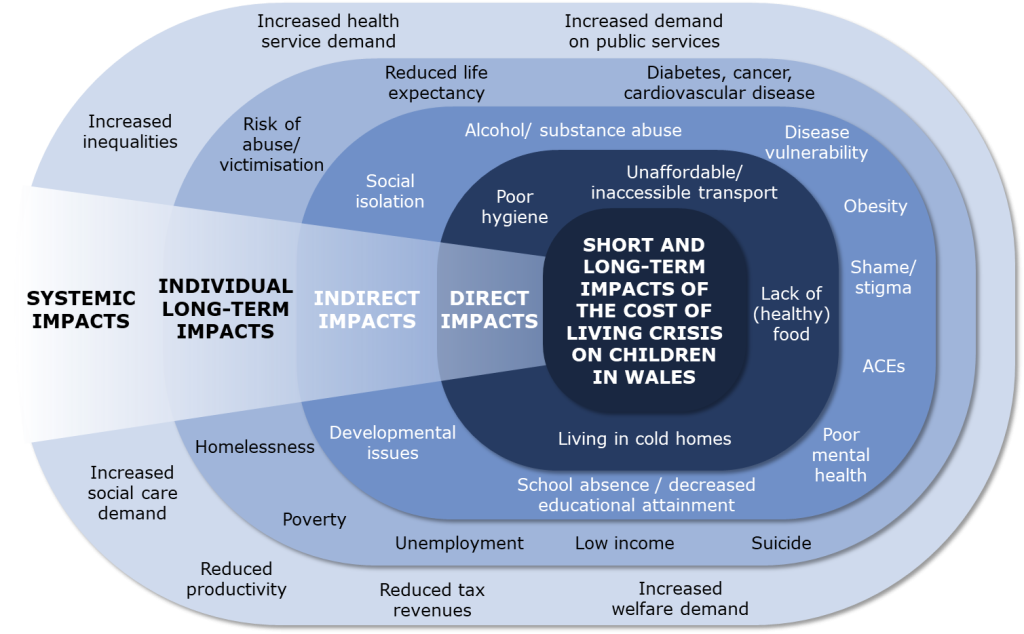

Evidence shows the cost of living crisis is compounding the impacts of child poverty on children’s development now, and their outcomes in later life, resulting in:

- a decrease in the life expectancy of children growing up in the worst-off areas of Wales over their life-course;

- existing inequalities in health between the worst off children and those living in better off areas of Wales becoming more entrenched; and

- some children and families being trapped in generational cycles of poverty and disadvantage.

Conceptualisation of the public health impacts of the cost of living crisis on children in Wales

How can health equity outcomes for children be improved?

The Welsh Government is currently developing a revised Child Poverty Strategy for Wales. This provides an opportunity to renew efforts to reduce child poverty in ways that are effective, evidence-based and that reflect the added challenges posed by the cost of living crisis.

Priority policy areas for action

Public Health Wales’s analysis identified 11 priority areas for action to reduce the impact of child poverty and the cost of living crisis on health inequity among children in Wales, both now and into the longer term. The proposed policy action areas aim to support and build on work that is already underway at a national and local level to address child poverty, the cost of living crisis and their impact on children’s health and well-being.

See below example initiatives that provide financial support for children and families, support community food organisations to reduce food insecurity, and that reduce the cost of school attendance. The examples have short-term impacts (e.g. reducing financial stress in the family) which contribute to longer term, positive knock-on effects on health equity (e.g. by improving children’s future access to well-paid work through improving school attendance and educational attainment in childhood).

Example 1

Between 2009-2011, the UK Government provided a lump-sum £190 payment for all pregnant women, with the aim of helping them afford nutritious food during pregnancy and decreasing stress. A study found that babies born to mothers who received the grant were 3-6% heavier and 11% less likely to be born prematurely. A larger effect was seen among babies born to low-income, younger mothers. These improvements in babies’ health were likely to have been due to the grant reducing stress for pregnant women. The findings show that there are clear health gains to be made from starting universal child benefits in pregnancy. It also shows that small, early interventions have the potential to reduce inequality in the long run, with high returns on investment.

Example 2

The Scottish Government, in response to evidence that emergency food aid ‘is not a long-term solution to food insecurity’, set up the Fair Food Transformation Fund (FFTF). The fund aims to encourage a move away from emergency food aid to provide community-led, long-term solutions to food insecurity. A review of FFTF concluded that most of the 19 case study projects successfully broadened their emergency food provision offer into community-based ‘food justice’ projects that embrace the social value of food.

Example 3

In Glasgow City Council, families who are eligible for school uniform grants are given the payments automatically, based on their eligibility for housing benefit and council tax. An automatic opt-in system would also be possible in Wales, as local authorities hold the necessary eligibility information.

Conclusion

Public Health Wales hopes that the policy action areas and case studies included in our children-focused cost of living report, along with our previous report which looked at the public health implications of cost of living crisis across the whole population, can help inform the development of the revised Child Poverty Strategy for Wales and provide a framework for prioritising the health and well-being of children during this time of crisis while also setting a course for a healthier and more equal future for Wales.

References

Welsh Government. (2023). Relative income poverty: April 2021 to March 2022. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Roberts, M., Petchey, L., and Morgan, L. (2023). Children and the cost of living crisis in Wales: How children’s health and well-being are impacted and areas for action. Cardiff: Public Health Wales.

Roberts, M., Petchey, L., Challenger, A., Azam. S., Masters, R., and Peden, J. (2022). The cost of living crisis: A public health lens. Cardiff: Public Health Wales.

Reader. M. (2023). The infant health effects of starting universal child benefits in pregnancy: Evidence from England and Wales. Journal of Health Economics, 89, 102751.

Hammond, C. (2018). Review of the Fair Food Transformation Fund for Scottish Government. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Children’s Commissioner for Wales. (2019). A charter for change: Protecting Welsh children from the impact of poverty. Port Talbot: Children’s Commissioner for Wales.