Tackling Child Poverty: A Scottish Policy Model

August 26, 2025

This spotlight feature analyses Scotland’s approach to tackling child poverty through policy, investment, and adopting a public health lens, offering lessons for other countries.

Child poverty in the UK

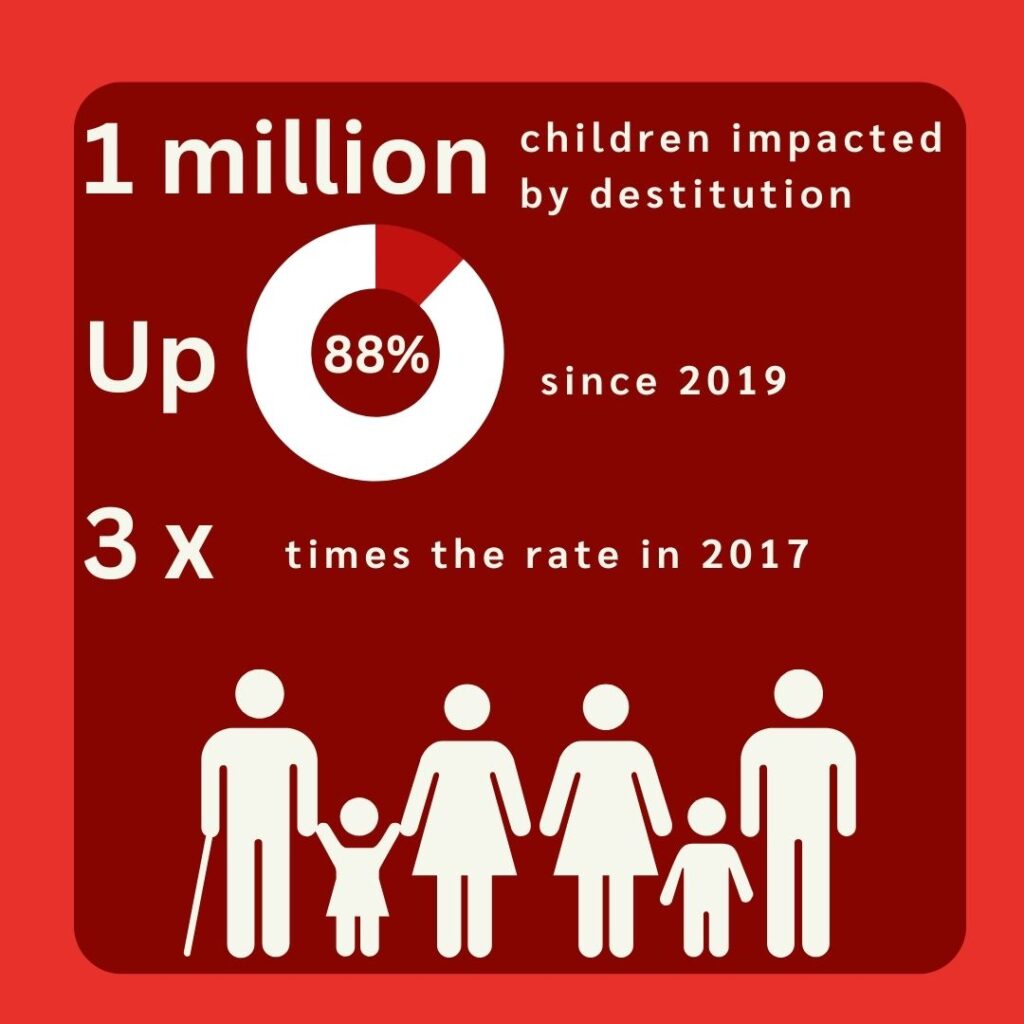

The Joseph Rowntree foundation, an independent social change organisation aimed at solving poverty in the UK, have reported that 3.8 million people in the UK are experiencing a state of destitution, meaning they are unable to meet their most basic physical needs such as staying warm, dry, clean and fed. Destitution is described as the deepest and most damaging form of poverty and is on the rise.

Figure 1. Statistics on children impacted by destitution. Source: Joseph Rowntree foundation.

Child poverty has fallen in only 12 of the 650 constituencies of the UK over the past 10 years, all of which are in Scotland. According to the latest UK Government statistics and as reported on by Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), Scotland is the only country in the UK where average year-on-year poverty rates are improving.

The health and wellbeing benefits of child poverty reduction

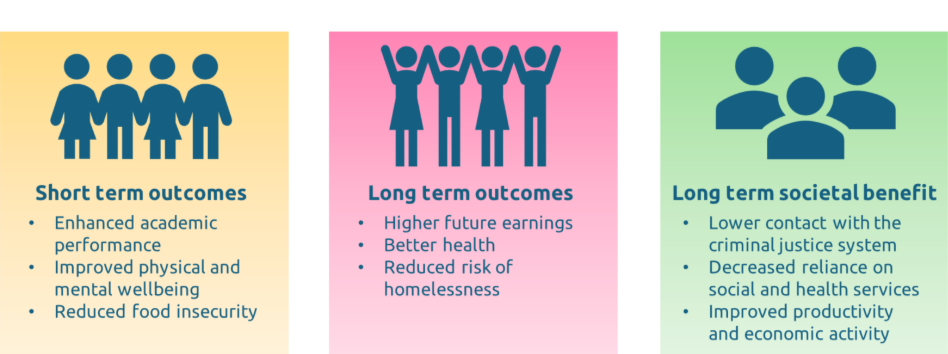

Public investment in policies and programmes to alleviate child poverty has been shown to significantly improve outcomes for children in the short and longer-term, with knock-on benefits for wider society (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Child poverty outcomes from public investment. Source: Smeeding, T. and Thévenot, C., 2016.

Scotland’s approach

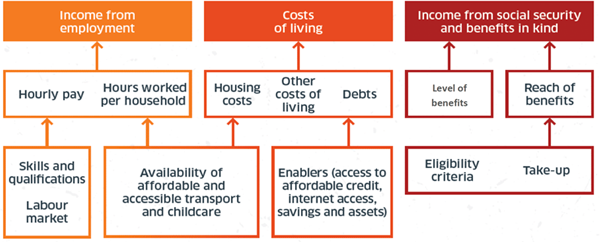

Scotland’s approach, established under the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017, focuses on prevention by targeting three key economic drivers (see Figure 3) of poverty: income from employment, cost of living, and social security.

Figure 3. Child poverty drivers. Source: Scottish Government.

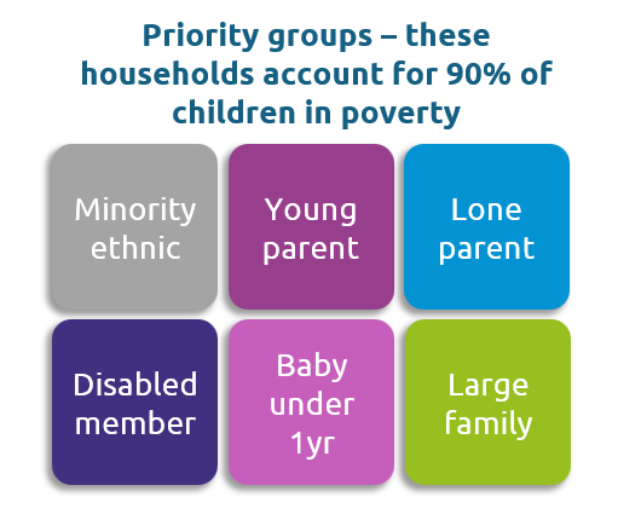

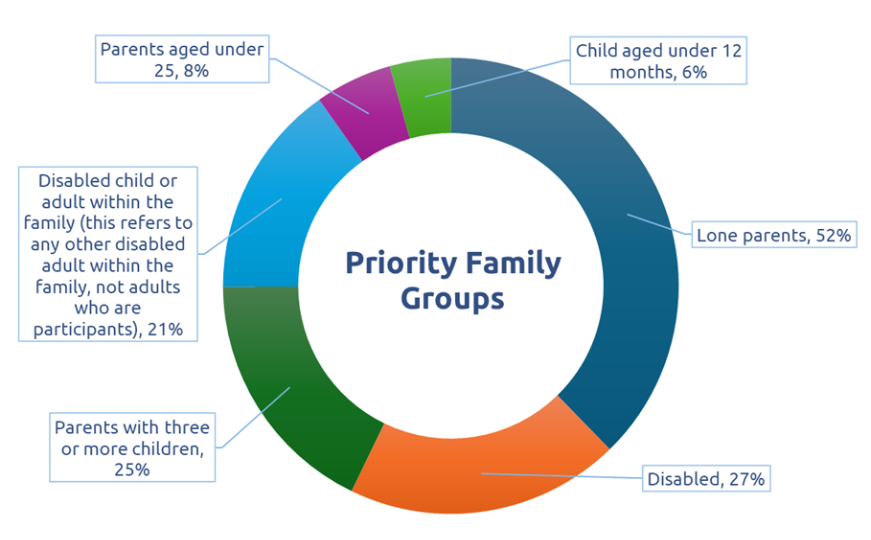

The approach prioritises families at greatest risk, defined across six specific groups (see priority groups – Figure 4), and is supported by statutory income-based targets, independent oversight, and mandatory national and local action plans. Scottish government modelling suggests that Scottish policies have prevented approximately 100,000 children from falling into poverty in the past year. The focus of these policies has been on income maximisation for low-income households.

Figure 4. Scottish Government six priority family groups at greatest risk of poverty. Source: Scottish Government.

Income from social security

The most immediate and largest impact on child poverty has come from the introduction of the Scottish Child Payment. It is an initiative for low-income families with children under 16, providing weekly payments per eligible child. Further increases to this payment has been independently modelled as the most cost-effective way to reduce Scottish child poverty. This has helped Scotland move closer to meeting their targets by reducing poverty, as measured by Scottish Government, in the short term and by helping families move nearer and above the poverty line. This can improve immediate living conditions and secure a longer-term trajectory out of poverty. Other child related devolved benefits exist such as Best Start Foods, available to pregnant women, and Best Start Grants; but the Child Payment reaches a wider group and represents a larger payment.

The Scottish government has taken the view that some UK Government policy decisions risk increasing child poverty and have sought to mitigate this by exercising their devolved powers. For example, they have fully mitigated against the bedroom tax (the reduction in housing benefit or universal credit applied to tenants in social housing who are deemed to have more bedrooms than required) for several years through the discretionary housing payment. Scottish Government’s own modelling and further analysis by CPAG demonstrates that the individual most cost-effective policy to reduce child poverty would be to end the UK Governments two-child limit, which Scotland aim to introduce mitigation for by 2026.

Strikingly, most families in the UK impacted by the two-child limit are from single parent households and families with income from employment. Further modelling by the Scottish government predicts that if the UK were to abolish the two-child limit, replicate Scottish Child Payment in Universal Credit and remove the benefit cap, this would lower child poverty by 10% in Scotland, which represents lifting 100,000 children out of poverty.

Income from employment

Scotland’s approach highlights the pivotal role of health boards as anchor institutions—key players in creating sustainable jobs, shaping procurement practices, and optimising the use of their estates to benefit local communities. Scottish Government and Public Health Scotland, collaborating closely with Directors of Public Health and the Anchors programme, now in its second year, aim to target the root causes of health inequalities. This is achieved by actively promoting fair employment opportunities for priority groups (see Figure 3 for groups), directing spending towards local goods and services, and partnering with community organisations to maximise social and economic impact.

For example, NHS Tayside utilises its estate at the Strathmartine Centre in Dundee to support learning disability services through community gardening and occupational therapy programs, demonstrating how health assets can drive local employment and wellbeing.

This builds into Scottish government’s Community Wealth Building agenda, which focuses on fostering economic development that generates, circulates, and retains wealth within local communities. The Community Wealth Building (Scotland) Bill, introduced in March 2025 and currently in stage 1 of enactment, formalises this commitment.

Scottish government also funds the Parental Employability Support Fund (PESF) under their child poverty strategy and their No One Left Behind strategy (NOLB). It is jointly managed by Scottish and local governments and offers tailored assistance to low-income families identified as priority groups (see Figure 3 for groups), to help parents overcome barriers to sustainable employment and improve household incomes.

NOLB has shown an increase in the numbers supported every year with a total of 23,465 parents supported since April 2020. As of December 2024, a quarter (26%) of parents in receipt of NOLB support entered employment and a further third (31%) had other positive outcomes such as gaining further qualifications, training and work experience. Importantly, Scottish Government have shown that the support is reaching Priority Family Groups (See Figure 4).

Figure 5. Priority Family Groups in receipt of NOLB support from July-September 2024 (some adults may appear in one or more of these family groups). Source: Scottish Government.

Cost of living solutions – including childcare, food, and transport

Scotland is the only part of the UK to offer 1,140 hours of funded Early Learning and Childcare (ELC) annually to all 3- and 4-year-olds, as well as eligible 2-year-olds, regardless of parental employment status. In September 2022, an estimated 99% of eligible 3 and 4 year olds were registered for ELC, up from 97% in 2021.

Scotland has in place various other initiatives to support with the cost of living for families, with some of these listed as examples below.

- Universal free school meals are provided for primary school children during their first five years of primary education. From March 2025, children in the final two years of primary school who receive the Scottish Child Payment will also be eligible, extending means-testing into early secondary education. Wales remains the only UK nation to offer fully universal, non-means-tested free school meals for all state-funded primary schools.

- Cash-First – approach that tackles food insecurity by prioritising direct financial support over food bank referrals. This includes cash transfers or vouchers combined with advice and support, designed to help individuals manage their income and avoid future crises. This strategy aims to empower people to make their own spending choices rather than relying primarily on food banks.

- The School Clothing Grant supports parents and carers of primary and secondary school children who are receiving certain benefits, helping to ease the cost of school uniforms.

- Scotland’s ‘Five Family Payments’ include the Best Start Grant (Pregnancy and Baby Payment, Early Learning Payment, School Age Payment), Best Start Foods, and the Scottish Child Payment, all designed to provide financial assistance at key stages of a child’s development.

- All young people aged 5 to 21 can apply for the Young Persons’ (Under 22s) Free Bus Travel Scheme, which aims to improve access to education, employment, and leisure by making transport more affordable.

CPAG’s annual Cost of a Child report finds that these policies can reduce the net cost of raising children by over a third for low-income families when compared with the rest of the UK. The payments have narrowed the gap between income and the cost of living for families, helping to raise children at a more socially acceptable standard of living.

Despite these positive measures, critics argue that investment has been disproportionately higher in social security compared to other crucial areas like childcare and housing costs and creating an economy that offers decent jobs for parents. Housing costs, in particular, remain the largest financial burden for many low-income families.

Reporting and accountability

Using local evidence to drive local solutions: The Scottish Annual Action Reports

Annual Local Action reports have developed from being a minimum statutory requirement for health boards and local authorities to report on activity around income maximisation, to a mechanism for improving practice year on year through feedback loops with Public Health Scotland and the Improvement Service for local government. The feedback includes the sharing of good practice and identification of impactful work that should be scaled up. It has also led to the greater focus on tackling the drivers of child poverty, not just mitigation. It has enabled consideration of how health boards can operate as anchor institutions and how priority families (see Figure 3) can be effectively targeted. This has benefitted from engagement with system leaders, particularly Directors of Public Health and child poverty leads in health boards.

2030 child poverty targets

The Scottish Government set legally binding targets for itself, local authorities, and NHS health boards to reduce child poverty by 2030, against four income-based indicators, so that less than:

- 10% of children are in relative poverty.

- 5% of children are in absolute poverty

- 5% of children are in combined low income and material deprivation

- 5% of children are in persistent poverty

Scotland has established a legal framework for tackling child poverty and meeting its 2030 child poverty targets through the publication of three Child Poverty Delivery Plans; “Every Child, Every Chance” (2018-2022) and “Best Start, Bright Futures” (2022-2026) and is currently developing the third delivery plan for 2026-2031. The plans are part of the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017, which requires the Scottish Government to report on its progress annually and are accompanied by an evaluation strategy setting out the approach to assessing progress towards meeting the 2030 targets. The overarching approach comprises three layers of measurement. Firstly, poverty rates across all four targets. Secondly, monitoring key indicators for each of the known drivers of poverty. Thirdly, individual evaluation of key policies to better understand the contribution they are making towards the targets. In addition to understanding the individual impact of policies, Scottish government recognise the need for policies to work seamlessly together and have a focus on evaluation of systems change.

Conclusions

Scotland’s experience offers valuable lessons for Wales and other countries. The introduction of statutory duties and income-based targets have helped maintain a strong focus on child poverty, raising its profile and deepening public and political understanding of both its impacts and the potential solutions. Whilst high level targets have merit, crucially, the approach also incentivises progress in supporting families in the deepest poverty, ensuring that efforts are directed towards those facing the most severe disadvantage.